I was born the year before Dr. King was assassinated: a middle-class white boy, living in a quiet neighborhood full of long-leaf pines on the outskirts of town. Talladega, Alabama knew it’s share of racial tension. It is, after all, home of the largest tri-oval track on the NASCAR circuit, as well as home of Historically Black College, Talladega College: a sort of micro-cosm of the American racial experience.

And I was a classic white moderate, president of the FFA, and won a state public speaking contest in Montgomery on the glories of free-market capitalism. I was never openly racist. I was generally nice. I did not make a habit of using the n-word.

And it’s true that “one of my best friends was black.” I sat behind him in first grade, and that was the start of our friendship. I remember him helping me read the chalkboard. My vision had already begun to deteriorate, but I did not yet have glasses. We would go on to have many years of laughter and conversation and good-will pass between us. I still smile whenever I think of his own beautiful smile which he generously shared with our classmates.

But we never spent the night at each other’s homes. There were unspoken boundaries.

And we had a black housekeeper, for whom I felt much affection. She seemed to love me. But there too, there were boundaries, typically unspoken.

There were, in other words, dynamics I knew, but I could not apprehend. I could see them. But I did not see them.

I was white, relatively privileged, smart, morally circumspect, and worked hard. My parents were loving, wonderful, beautiful people who worked hard, went to church every time the doors were open, and taught us to be respectful and polite to everyone.

Life in that town was easy for me, and I enjoyed it.

And, consequently, when I saw a confederate flag, it did not say “racist” to me. It was a cultural artifact symbolizing my love for Alabama, and friend chicken, and the foothills of the Appalachian mountains, and Merle Haggard, and people speaking to each other on the sidewalk. When we made fun of Yankees, it was with no conscious racist intent. It was simply a cultural defensiveness: We knew that when New Englanders or Mid-Westerners hear your southern accent, that their assessment of your IQ immediately drops 10 points.

We did not merely know this. We could apprehend it, because we experienced it. When my wife and I moved to the mid-west for me to work on a Ph.D., she had just finished her MBA. And prior to her work in grad and undergrad programs, she ranked near the top of her class at one of the best prep-school’s in the country. Nonetheless, when she found herself in a bank in the mid-west, opening up a checking account, the bank representative condescendingly held up a debit card in front of Laura, and said, “now this is an ATM card.” She placed the card on the desk, and with two fingers slid the card deliberately across the desk toward Laura, and said: “do they have these down home?”

I had no problem seeing the bias and the condescension. It didn’t matter whether the mid-westerner said there was no bias, no ill intent, no prejudice. I could in fact really see it, could apprehend it.

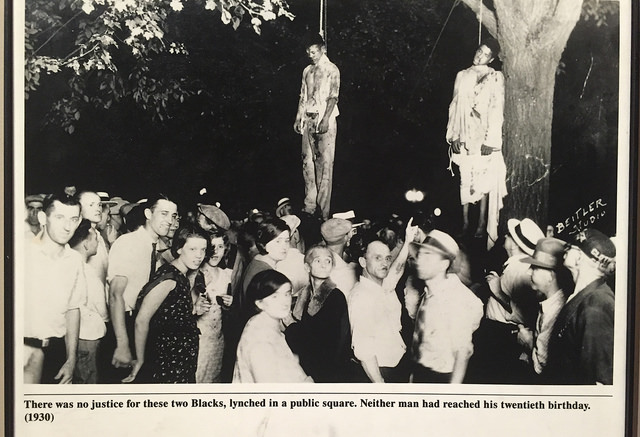

Sure, I saw race as a boy in Alabama. I knew where the boundary was between “n***** town” and the rest. But I could never see any of it, could never apprehend it, because I was, as it were, on the other side of the desk.

I first became aware of my own unconscious bias when I was a seminary student. I ran a traffic light and hit a pick-up truck. The truck spun around, slammed up against the curb. I was frightened and dazed, angry at myself for being so stupid. I pulled over to the curb. I saw that the driver was a young black man. Unbidden, and shocking to me, the words formed clearly in my mind: “oh no. He’s black. He’ll sue me.”

I was ashamed then of the unbidden impulse, and I am embarrassed to tell the story now. But it was an important moment, because I began to see myself, and thus my world.

During those same years in seminary, one of my faculty mentors showed us some of the clips from the documentary series “Eyes on the Prize.” I learned of the fire bombing of a bus, one of the famed Freedom Rides, May 14, 1961.

What shocked me was not merely the meanness and violence of it: it was that this famed historic incident had occurred some fifteen miles from my childhood home. Here I was, maybe 24 years old, and five hundred miles away in another state, seeing these pictures for the first time.

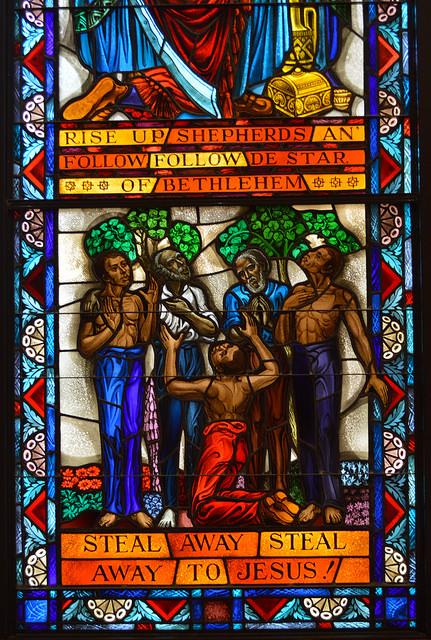

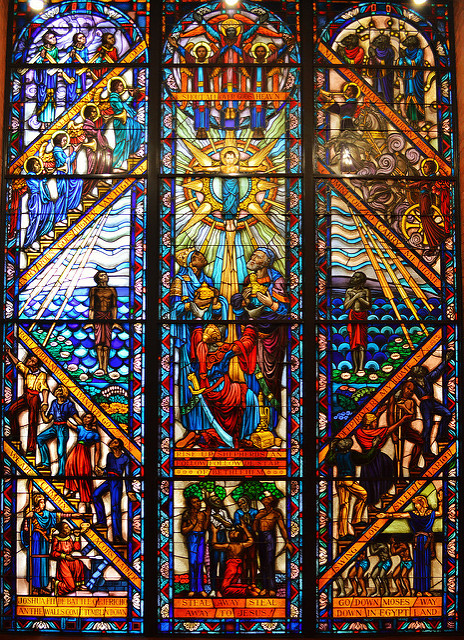

16th Street Baptist, Birmingham, Alabama

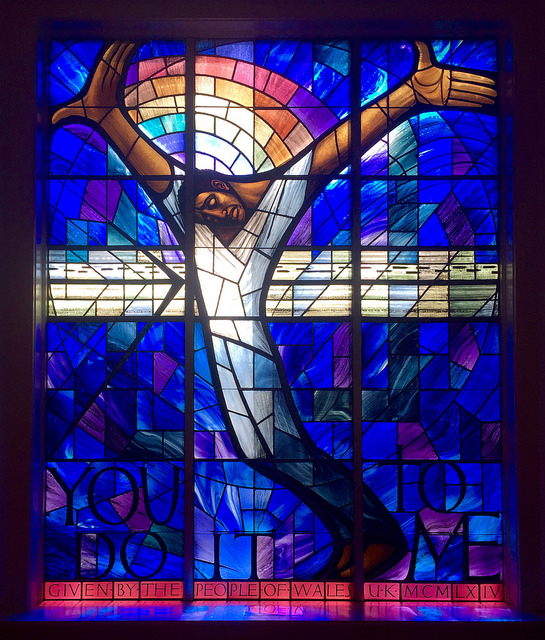

There would be many more such incidents of having my eyes opened. And some of the most important moments would be the trips I have taken with my colleague David Fleer: we’ve taken students and church friends on pilgrimages. Each trip more scales fall from my eyes, to allow me to see things, apprehend things I could not have otherwise.

We stop at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, the staging ground for the children’s march that would finally prompt Bull Connor and his minions to call out the dogs and the fire-hoses. It is where ten sticks of dynamite killed four little girls getting ready for church on a beautiful Sunday morning.

We make our way to Selma, to Browns Chapel, the staging ground for the famed show down at the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday, which would finally give way to a long slow march to Montgomery. It is the site of Malcolm X’s last major address before he was assassinated.

We stop in Montgomery, at the site of a former slave warehouse. Kidnapped from their homes, the Africans housed there had made their way through the middle-passage of the slave ship and the Atlantic, then loaded onto steam ships and hauled up the Alabama River, where they were unloaded as cargo and prepared for auction.

They would be shuffled in shackles to the bottom of Dexter Avenue, a poignant site saturated with historical significance. From there at the bottom of the hill one may see the Alabama State Capitol at the top. Beneath its long shadow, there at the bottom of the hill was the slave auction block; and, the hotel in which Jefferson Davis stayed the night before his inauguration as President of the Confederacy; and, the building which housed the telegraph office from which the order was sent to fire on Fort Sumter, to begin the Civil War; and, the bench on which Rosa Parks sat before she boarded the bus and took a seat which she would not give up.

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

And just up the street sits Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, the first church assignment for Martin Luther King, Jr. It’s humble redbrick sits quietly but auspiciously beneath the proud white Capitol.

We see Tuskegee, and visit with the ever-gracious and generous Fred Gray, attorney for Rosa Parks and MLK, who would successfully argue multiple cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and who had as a young man made a vow to return to Alabama after law school and “destroy everything segregated I could find.” We sojourn to Jackson, Mississippi where are regaled with tales by journalist Jerry Mitchell, who has been responsible for justice being served in all manner of old and cold Civil Rights cases. Or we visit with John Perkins, giant of a man and lover of God and neighbor. And we take our last stop in Jackson to be quiet and listen again to the horrific story of the cold-blooded assassination of Medgar Evers, standing in his own drive way.

Lorraine Motel, Memphis

And then on to Memphis, stopping at the Bishop Mason Temple, where Martin King made his last speech, one which still draws me to tears every time I hear it read, him telling the tale of the little girl who wrote to tell him she was “just so glad he didn’t sneeze,” him telling how he longed to see the Promised Land, but he didn’t know if he would get to see it, but that he had, like Moses, been granted to go up to the mountain top, to see the other side, and though he wanted, like all his brothers and sisters, to live a long life, he didn’t know whether God would grant it.

In less than 24 hours, he too would be assassinated, standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

Flannery O’Connor has a short-story entitled “The Life You Save May Be Your Own.” That phrase often rattles in my mind: I don’t know if my teaching and writing ever does a great deal of good for others—though I always hope it does. But I do know that it’s possible that the only life I really save through all this is my own.

I read and listen and write and take photographs so I can see, and apprehend. In Birmingham and Selma and Montgomery and Tuskegee and Jackson and Memphis, through Evers and Perkins and Parks and Gray and King, I get bits of apprehension, which allow the possibility for me to see who I am, where I’ve come from, and the human being I long to become.

Published previously on Tokens Show.